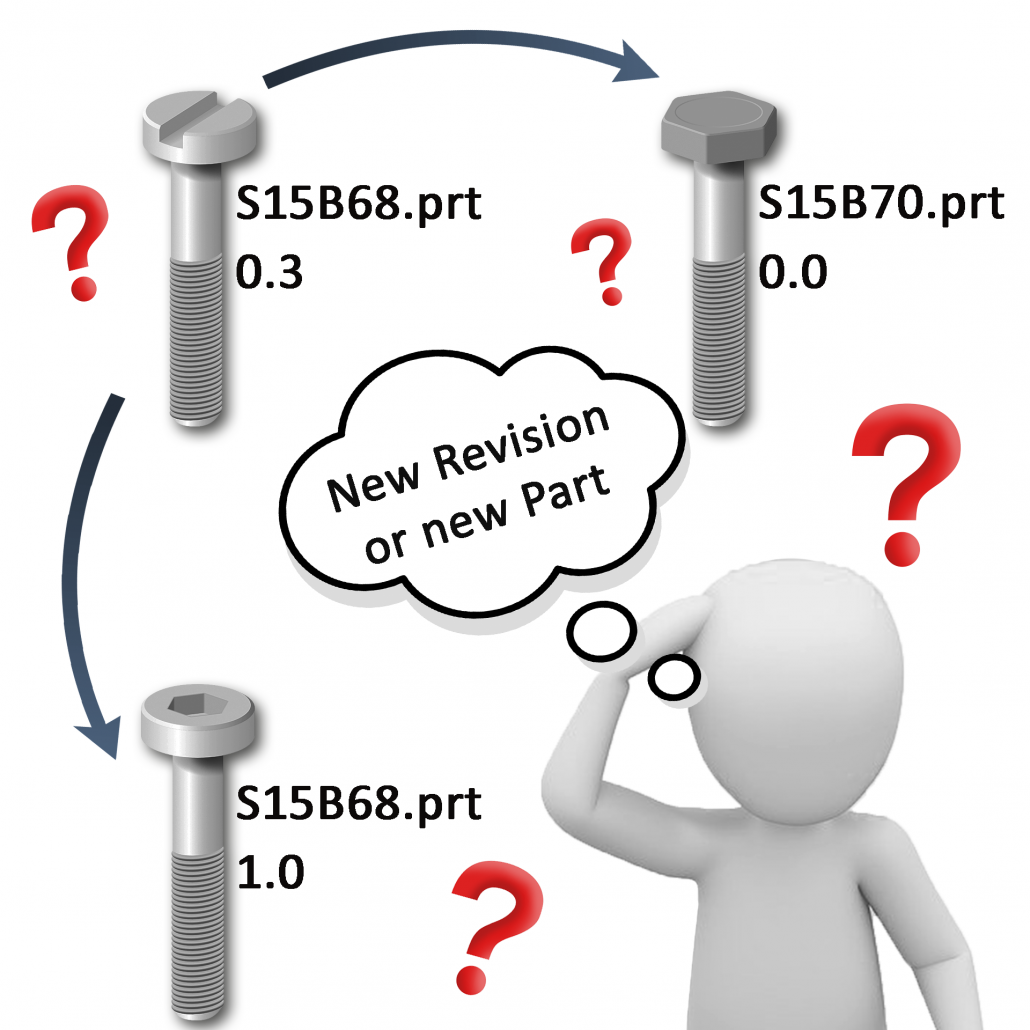

…that is often the question when product components must undergo a design change. Basically, there are always two options available: Pull a new part number (or PIN = part identification number) and create a part that replaces the previous one. Or revise your existing part in revision X and create a revision X+1 from it. So, which one should it be?

Form, Fit and Function

Well, if you go by the book, you use the good old FFF-criteria:

- Form

Determined by the size and shape but also by visual appearance (color, texture…) of your component part. Physical parameters (mass, center of gravity…) may also be a factor. - Fit

Describes how the part is integrated with other components in the final assembly, i.e. how it interfaces, connects, locks with other components. - Function

This is the function that the part is supposed to fulfill, its reason for existence, if you will.

So, if form, fit and function change, go for a new part number, if they do not, revision up.

Interchangeability

The idea behind the FFF-criteria, is to capture whether there is complete interchangeability between existing and new part. Interchangeability is really what you should think about when making your decision. Bear in mind though, these criteria are by no means universal and their specifics always depends on your organization’s processes and on your products. Especially the “Form” part of the FFF criteria is often debatable. For example, if you decide to go for a different, more cost-efficient finish on one of your steel components, this is strictly speaking a change in form. But does it really warrant a new part number with all the ripple down effects in your ERP, in upstream BOMs, in supplier communication etc.? Well, as so often, it depends. If your component is clearly visible in the product delivered to the customer – say, if it is the housing of a wristwatch – you most likely want to give it a new PIN. If however, your component does its job in the inner workings of your system – and if there is no impact to its fit and function – you may just decide to keep that part number and to revision up. Even changes in shape may be acceptable, such as adding pockets to reduce weight, so long as the change does not impact your production process, your product, or your customers perception of it.

Identification and stocking

Another way to think about interchangeability, is to imagine what would happen, if you stocked existing and changed components in the exact same location. Say you just dropped those new parts into the same container as the old ones, where they all happily mix and mingle. If it is of no concern which part is getting pulled from the container during production, then you can certainly do without a new part number. Put another way, the only part identifier needed for your inventory and production process should be the PIN; the revision should be completely irrelevant. This does not mean your company does not track revision usage at all. Modern PLM systems can track part effectivities by date, lots, serial numbers, and other criteria, so you know when certain revisions were introduced in the manufacturing process. But it is usually not required to trace every single component down to the revision level in the final product. Consequently, it should not be required to mark the revision on any component part; the part identification number should be quite enough.

Bad reasons to rev up

Demanding complete interchangeability, you may argue, could result in many new part numbers, too many perhaps, even if only “minor” changes – from an engineer’s perspective – were made to the component. True, but is pulling a new part number really that expensive in your company? If it is, you should better review your numbering process.

Another argument often heard in favor of revving up vs. new numbers is that revisions provide better traceability. Seeing that sequence of part numbers with their revisions gives you a nice overview of the history of this part. True, but the history is meaningful only if it is in fact the same part throughout the history! If the rule of interchangeability is violated, how can you see that from the parts history? Not so easy, unless you investigate the details of the change request that triggered the change. Moreover, most PDM/PLM systems provide means to copy new parts from existing ones while keeping track of the copy process. Like this you do know the origins of your new part design. If you have a good system, it even provides you with visual support to see the “family tree” of your parts at a single glance.

You may argue that the part number together with its revision always gives you the unique component you are looking for. So why not just use that combination to identify the right part in production, inventory etc.? Well, you can do that, and it is not an uncommon practice. But essential, this is just introducing a more complex, semi-smart numbering schema, where the combination of PIN and revision becomes the new part number. Better stick to the convention that the part is identified by the PIN, no matter the revision.

Summary

As you probably expect, there is no simple, single rule to decide whether you should go for that new PIN or to just rev up. Certainly, interchangeability is the best single criterion you can use, but how that should be defined in your company, is up to you. If the following holds, you are probably good keeping that PIN and to simply rev up:

- Interchangeability: New part revisions can be used wherever the previous revision was used

- No “significant” change in Form, Fit, Function

- Inventory has no need to stock based on part revisions

- No need to mark the revision on your part